Any list of cognitive “wonders of the world” would have to include Micronesian navigation. For centuries, seafarers in the region would push off from tiny specks of land, perched on small canoes. After days in the open water, amid the welter of waves and weather, they would arrive exactly where they meant to: on other specks of land, sometimes hundreds of miles away [1]. They did this without GPS, without clocks or magnetic compasses, and without detailed charts. Their navigational tools were in the world and, especially, in their minds. They relied on the stars, which—when construed a certain way—furnished a “sidereal compass.” They relied on close observation of birds and marine phenomena. And they relied on a diverse kit of conceptual tools—powerful ways of organizing and remembering information—some so exotic and perplexing to Western eyes that they remain dimly understood. They relied, for instance, on the triggerfish.

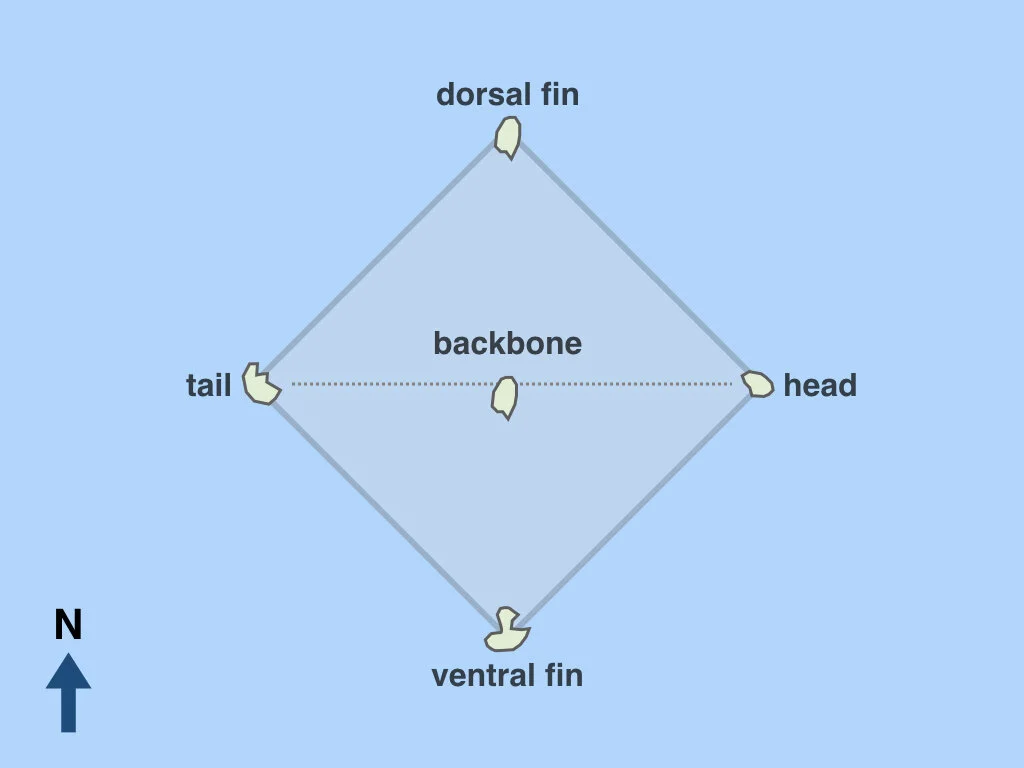

The triggerfish is a common marine creature in the region, but also a powerful schema for organizing spatial knowledge. At base, it’s an analogy—a way of understanding a new or slippery conceptual structure in terms of another, more familiar structure. Here’s how it worked. Picture a triggerfish, lying on its side on the sand. Colorful and filigreed as such a fish may be at first glance, it may also be boiled down to a barebones structural essence. It has a top (dorsal) fin and a bottom (ventral) fin; it has a tail and head, and a backbone that connects them [2]. Seen in this boiled down way, it becomes an abstract spatial template, which Micronesian navigators could then project onto the marine geography around them. That is, any group of islands arranged in roughly this diamond shape could be seen as forming an imaginary triggerfish. With this grouping device in hand, a vast land-speckled ocean becomes much more manageable.

The basic triggerfish schema, projected onto a group of five landmarks—in this case, all islands.

Our understanding of the triggerfish system remains incomplete—available reports are based on interviews with just a couple navigators [3]. But we can reconstruct a few further details. For one, the fish always faces east. In other words, if you’re construing a set of landmarks as a triggerfish, the eastern-most landmark will be the head and the westernmost one the tail. (However, as discussed below, the dorsal and ventral fins are not always north and south, respectively.) Another notable feature of the system is that not all the key locations on the fish need to correspond to islands. They could be reefs or other seamarks. In some cases they seem to have been quite fuzzy: “the place of the whale with two tails,” or an area of rough water associated with “the personal name of a frigate bird” (see Riesenberg, 1972). Sometimes the participating landmarks were islands that don’t actually exist—so-called “ghost islands,” which played a prominent role in Micronesian lore [4].

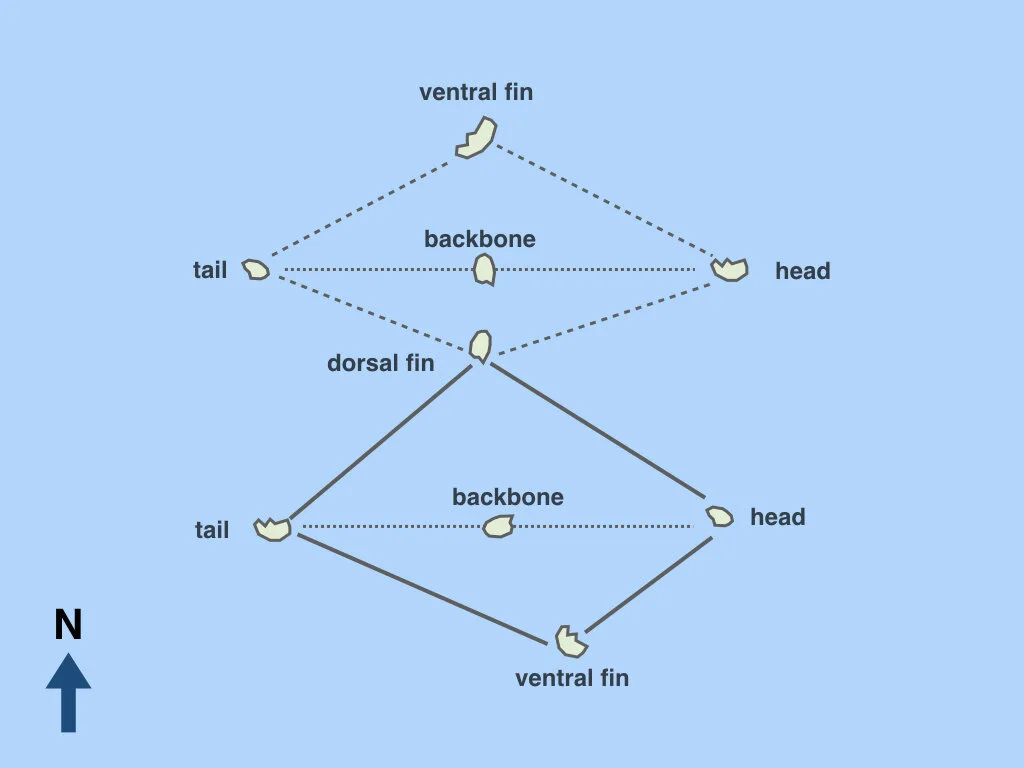

Another key aspect of the triggerfish technique is that you can build off the basic five-part schema to create larger spatial structures. This can be done in a few ways. One is by “flipping” the triggerfish. Suppose you have a southerly set of five landmarks and four more landmarks to the north, which share a central landmark—the dorsal fin of the southerly fish. You than imagine this cluster as actually one fish, which gets flipped over to the north [5].

The technique of “flipping” the triggerfish. A larger cluster of islands—in this case, nine—can be imagined as one triggerfish that is flipped over across its dorsal fin.

Another way to create bigger structures is to “tie” a series of triggerfish together such that the backbone of one triggerfish corresponds to the ventral fin of another, forming a concatenation of overlapping fish. Riesenberg (1972) discusses one such concatenation, comprising 17 landmarks. Remarkably, only seven of the 17 are actual physical islands—the rest of the structure is filled out with reefs, seamarks, and “a mythical vanishing island which is the subject of various stories around the Carolines” (p. 31-2).

Given the spottiness of available accounts, we can’t be sure how often these “flipping” and “tying” techniques were used. Nor can we be sure about other aspects of the system. For instance, it seems that certain triggerfish were conventionally fixed in certain regions, with a particular island always talked about as the head of a widely known triggerfish. But an apparent advantage of this mnemonic device is that it’s potentially highly flexible—any suitable set of landmarks might be construed in this way—so it’s also tempting to assume the system was used broadly and variably. Current accounts do hint at some degree of idiosyncrasy in how the system was deployed.

One thing we can be relatively sure of is that the system was foremost a tool for committing marine geography to memory (rather than as a navigational device used in situ). Riesenberg (1972) writes that his informants were unanimous in describing the triggerfish system as a “teaching device” whose purpose was “to remember how the various places covered by these imaginary fishes are oriented in relation to each other” (p. 32-3). Nor was the triggerfish the only mnemonic used in this way. Others also relied on spatial analogies—in another, a group of islands was imagined as a row of six whales, each with some distinctive feature.

It’s worth lingering a bit on the question of why Micronesian navigators would indulge in all this whimsical imagining. Wouldn’t it be more straightforward, not to mention more accurate, to just remember the actual “veridical” layout of these landmarks? Perhaps, but it would apparently be less useful. Humans everywhere like to think in terms of abstract spatial templates. We use them when we talk about S curves or figure eights; when we describe narratives as having an arc; when we see states as having “panhandles”; when we imagine a kinship structure as a crane’s foot (see the etymology of pedigree) or life as a branching tree. Spatial analogies like these are remarkably pervasive. And they are perhaps at their most powerful when they help us manage spatial information that would otherwise be cognitively unwieldy.

To appreciate the point, it may help to consider another unwieldy spatial array that humans have long struggled to make sense of: the night sky. For millennia, cultures around the world have sought to reduce the complexity of the sky by parsing it into more manageable, memorable chunks—that is, constellations. These often take the form of familiar animals such as tortoises, horses, ring-tailed possums, and, yes, fish [6].

The constellation Pisces. Illustrated by Sidney Hall in Urania’s Mirror (1824), a well-known set of star chart cards (source).

We can perhaps think of the Micronesian triggerfish schema as a kind of constellation of the sea (albeit a mobile one—it swims around). Seen in this way, it just one example of a wider set of techniques humans have invented, over and over throughout history, to help make a spatially vast and messy world a bit more manageable.

Notes

1. For a general overview of some of the most distinctive cognitive dimensions of Micronesian navigation, see Ed Hutchins’ 1983 chapter, ‘Understanding Micronesian Navigation.’ As Hutchins notes, societies in other parts of the Pacific also undertook long inter-island voyages, but their practices were largely lost after colonial contact. Only in Micronesia did the navigator’s traditional art persist into the 20th century, and so it is their tradition we can best reconstruct.

2. The status of the backbone in the triggerfish schema is a bit murky. In some accounts it is treated, like the other four landmarks, as a discrete labeled area to be named. At other times, it goes unnamed, perhaps because it is conceived as merely a path that connects the head and the tail. Interestingly, the “backbone” analogy also figures in traditional Pacific navigation techniques in other ways—see ‘The Secrets of the Wave Pilots.’

3. The most thoroughgoing discussions of the triggerfish system are found in Finney (1998), Riesenberg (1972), and in the Penn Museum’s online interactive (graphically dated but clearly presented). Other details and speculations can be found in Alkire (1970) and Hage (1978).

4. This is one of several Micronesian navigation techniques that involved imaginary islands. Another is the etak system, which Hutchins (1983) discusses in illuminating detail.

5. Some sources refer to the phenomenon of “Great Triggerfish”—see the Penn Museum discussion—which seem to be especially large imagined triggerfish that could span hundreds of miles. Another aspect of the flexibility of the triggerfish system is that it could be used on hugely different spatial scales, to involve imagined fish both great and small.

6. In fact, as Finney (1998) describes, Micronesian navigators also saw triggerfish in the sky: “The root of this term [for triggerfish], pwuupw, is polysemic with two main meanings, triggerfish (Rhinecanthus aculeatus) and the constellation Southern Cross (Crux), which are cognitively linked by their common diamond shape… The four stars of the Southern Cross correspond, respectively, to the mouth (head) of the fish and its dorsal (back), ventral (abdominal), and caudal (tail) fins” (p. 467).

Further reading:

Alkire, W. H. (1970). Systems of Measurement on Woleai Atoll, Caroline Islands. Anthropos, 65(1970), 1–73.

Finney, B. (1998). Nautical Cartography and Traditional Navigation in Oceania. In D. Woodward & G. M. Lewis (Eds.), The History of Cartography: Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies (Vol. 2, pp. 443–492). University of Chicago Press.

Hage, P. (1978). Speculations on Puluwatese Mnemonic Structure. Oceania, 49(2), 81–95.

Hutchins, E. (1983). Understanding Micronesian Navigation. In D. Gentner & A. Stevens (Eds.), Mental Models (pp. 191–225). HIllsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Riesenberg, S. H. (1972). The Organisation of Navigational Knowledge on Puluwat. The Journal of the Polynesian Society, 81(1), 19–56.

Tingley, K. (2016, March). The Secrets of the Wave Pilots. New York Times Magazine.