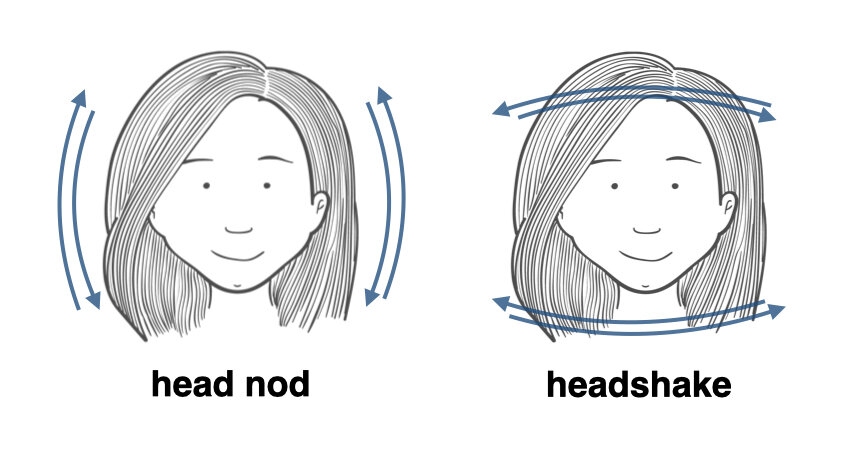

We’re all familiar with the nod: an up-and-down movement of the head, often repeated. It’s among our most commonly produced bodily signals, so common we barely register it. And we all know, of course, what it means: agreement, affirmation, sympathy. In a word: ‘yes’. But why do we make an up-and-down movement of the head to say ‘yes’? Why this particular pairing of action and meaning? A few thinkers—notably Darwin—have offered a sensible-enough explanation. But I think it’s wrong.

To set the stage, it’s helpful to start with a close cousin: the headshake. It has the opposite meaning, of course: negation, denial, refusal, distaste. In a word: ‘no.’ Charles Darwin was among the first close observers of the gesture. In The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), he suggested that this signal is rooted in how infants refuse food by turning away from a spoon or nipple, jerking the head to one side. Making repeated side-to-side actions is an effective way of deterring alimentary intruders, of conveying “Not interested!” And so, goes the story, we shake our heads to mean ‘no.’

The “we” here requires further comment, of course. As soon as Darwin set out to study bodily signals of negation and affirmation, he learned through his far-flung circle of correspondents that the headshake is not the only way people say ‘no’ across cultures. (For a catalogue of the negation gestures Darwin surveys, see p. 6-7 here.) But he noticed that many of the alternatives could also be plausibly traced to early actions of food refusal. For instance, a quick backward jerk of the head—used for negation in parts of the Mediterranean—is another good way to rebuff a spoon in one’s face [1]. A variant of this signal used elsewhere involves jerking the head backward while sticking out one’s tongue—which, of course, fits the food-refusal hypothesis nicely. Zooming out, the proposal that the headshake and other negation gestures trace to food rejection in infancy is widely accepted today [2]. Few other suggestions have been floated, in fact.

But what of the head nod? It would make sense that Darwin would try to pursue a similar explanation for our preeminent signal of affirmation. He observed that when his children took food into their mouths, they often inclined their heads forward. This action when repeated looks, of course, quite like a nod. And so he concluded that the nod, just like the headshake, has a “natural beginning.” Researchers since have echoed this account [3]. René Spitz, one of the most thoroughgoing scholars of bodily affirmation and negation, also traced nodding and head-shaking to nursing movements.

But there may be reasons to doubt the “natural beginnings” proposal. It turns out there are some interesting differences between head-shaking and head-nodding—differences that were unnoticed or skated over in earlier investigations and still don’t seem to have attracted much attention. Taken together, these differences cast doubt on the idea that both these both basic head gestures gestures are rooted in early feeding routines. They constitute clues, in other words, that something else could be going on.

A first clue is that children around the world start to use the headshake a fair bit before they start to use the head nod. In one recent analysis, Michael C. Frank and colleagues examined parental reports of early gestures in English, French, Korean, Slovak, and several other languages. They found that the average age of onset is 10.3 months for head-shaking and 14.5 months for head-nodding. Four months may seem like a slim difference, but it’s a substantial this early in development. Now it’s important to note that children also say “no” verbally before they say “yes.” So part of the lag is likely that children have a greater need to reject and refuse than they do to accept and affirm [4]. But the delay in acquisition is large enough that communicative need may not fully account for it.

A second clue: Blind children shake their heads but do not seem to nod. A 2000 study by Jana Iverson and colleagues compared five congenitally blind and five sighted children (aged 14-28 months). There were two common gestures not used by the blind children: the shrug (interestingly—see previous post) and the head nod. Similarly, a 2007 study with seven deaf-blind children, 4-8 years old, found no cases of head-nodding (but also, it should be noted, very scant use of the headshake). These reports actually go against Darwin’s own claim about the head gestures of blind children. He quotes a report of one blind child who “constantly accompan[ied] her yes with the common affirmative nod.” But I’m inclined to trust the more recent evidence over Darwin’s second-hand anecdote.

A third clue, which to my mind is the most telling: with the exception of the nod, most affirmation signals used across cultures don’t seem plausibly traceable to food acceptance. (Darwin does not acknowledge this fact directly but may have sensed it. He noted in passing that there seems to be a greater diversity of signals used for affirmation than for negation.) Darwin’s list of affirmation signals includes: a side-to-side gesture (likely the one famously used in Bulgaria and other Balkan countries, which reportedly resembles the headshake), a backward head jerk along with an eyebrow raise (which he reports as used in the Philippines and Abyssinia), an “elevation” of the head and chin (New Zealand), and a throwing of the head to one side (India). Just-so reasoning is famously inventive, but it’s quite difficult to concoct stories that relate these actions to food acceptance.

So then where do our affirmation signals come from? if the nod does not have a “natural beginning” as Darwin and Spitz proposed, what sort of beginning might it have? Ironically, I think the most compelling account is one based on an idea Darwin himself introduced in Expression, but didn’t think to apply to the case of affirmation and negation: the principle of antithesis. (This is the very principle he did invoke, by the way, to try to explain the shrug.) The idea goes like this. In some cases, you have two bodily signals that are naturally opposite in meaning. That is, the signals mean opposite things because they derive their meanings from actions that serve opposite functions. This is what we can think of as the “natural beginnings” proposal already discussed, that the headshake naturally means ‘no’ and the head nod naturally means ‘yes.’ But, in other cases, you may have two signals with opposite meanings where only one of the signals, the first one, has a natural connection to its meaning. The second signal merely derives its meaning purely by contrast with the naturally derived one. This is what we can think of as the “antithesis” account, and it’s what I think is going on here: the headshake naturally means no and the head nod derives its meaning by contrast from it. The nod has no natural meaning in other words, just a conventional contrastive one.

Two accounts of the origins of the headshake and head nod. The first (left) is the “natural beginnings account”—favored by Darwin and others—in which both signals are grounded in feeding actions. The second (right) is the “antithesis account”—proposed here—in which the headshake is naturally grounded and the head nod derives its meaning by contrast with it.

The “anthesis” account is clearly a better fit for the clues discussed above. If one signal serves to ground the other, you would expect it to appear first developmentally. (And, other things being equal, you would also expect a developmental advantage for naturally grounded signals over ungrounded ones.) The fact that blind children do not nod their heads is consistent with the idea the that two are not equally straightforward to acquire. In the absence of visual input, it’s presumably easier to pick up bodily signals grounded in action patterns. Finally, the “antithesis” account is a better fit for the cross-cultural data. Of the known negation signals, most can be plausibly connected to some natural signal for food rejection. Of the known affirmation signals, however, only nodding (and perhaps eyebrow-flashing) may be plausibly connected to some natural signal for food acceptance. The greater diversity in affirmation signals that Darwin noted parenthetically also makes sense. There may be only few ways to naturally ground a signal but more ways to form signals that contrast with grounded ones. For instance, if your negation signal is a single abrupt pull-back of the head—the Mediterranean jerk mentioned earlier—you could contrast with this by vigorous repeated nodding of the head, or perhaps with a side-to-side movement of some kind. As it happens, both these affirmation signals are attested.

It’s frankly a bit boggling that so few scholars have tried to explain the origins of one of our most commonly used gestural signals. Direct discussions of the issue are scarce. I’m not, however, the first to express skepticism about Darwin’s “natural beginnings” story. Kettner and Carpendale (2013) have written that, relative to head-shaking, “there is less evidence that a natural reaction might underlie [head-nodding]” [5]. To my knowledge, though, no one has previously articulated the specific antithesis account laid out here (notwithstanding my own brief mention of it). The next step is to figure out a way to test it.

Notes

1. The Mediterranean version of the backward jerk is reportedly sometimes produced with a tongue cluck. Darwin was puzzled by this added flourish. He wrote: “What the meaning may be of this cluck of the tongue, which has been observed with various people, I cannot imagine.” But this clucking action resembles a way of trying to dislodge peanut butter (or other substances) from the roof of the mouth, and so fits the his food-rejection story better than he realized. Note, finally, that Darwin also described negation gestures made by the hands—such as the side-to-side finger wag—which he very reasonably concludes that these are likely formed by imitation of the headshake.

2. One thing you might be thinking: What exactly does it mean to say that a gesture is “rooted in” or “has its origins in” or “traces to” some action pattern? It seems a straightforward claim from a distance, but a bit of a head-scratcher on second look. It could mean, for instance, that every infant invents the headshake from scratch, linking a particular action to a particular meaning. (This is unlikely—if infants were inventing these anew we would expect a lot of idiosyncrasy.) Or it could mean simply that some time—maybe many generations ago—a clever infant routinized the gesture out of the action pattern and it got established in the community. Now that it’s an established convention, infants today need not notice the grounding of the gesture to acquire it. Or it could mean that the infant comes to the gesture through its natural associations and, simultaneously, through its use as a convention in the community. So, for instance, children may be more likely to pick up the head-shaking convention because it’s easily linkable with a natural action pattern. These three explanations differ principally in whether they suppose the infant to be: (a) mostly conventionalizing an action pattern all by themselves; (b) mostly adopting a convention without linking it to an action pattern; (c) or some combination of the two. I favor the last option.

3. Roman Jakobson, taking a different tack, thought that the nod had a symbolic origin. He noted its resemblance to bowing and other bodily signals of deference, writing: “The movement of the head forward and down is an obvious visual representation of bowing before the demand, wish, suggestion or opinion of the other participant in the conversation, and it symbolizes obedient readiness for an affirmative answer to a positively-worded question.” He then goes on to propose, contra Darwin’s “natural beginnings” proposal, that the headshake is formed by contrast with this symbolically rooted nod. “The forward-bending movement used in an affirmative nod found its clear-cut opposite in the sideward-turning movement which is characteristic of the head motion synonymous with the word 'no'. This latter sign, the outward form of which was undoubtedly constructed by contrast to the affirmative head motion, is in turn not devoid of iconicity.” As we’ll see, I think Jakobson was right to emphasize the “antithetical” construction of these signals but wrong in his specific story.

4. For example, if you tend to just be given food, as young infants are, you don’t really need to nod to accept it but you may have occasion to reject it. If, on the other hand, you are offered food, or given a choice of foods, it’s helpful to be able to both affirm and reject.

5. Kettner and Carpendale (2013)—who present the fullest discussion of these issues I’ve been able to find—express general skepticism that either head-shaking and head-nodding are rooted in basic action patterns. We can’t take such skepticism too far because the cross-cultural prevalence of such signals suggests they have to be ground or motivated in some way. But Kettner and Carpendale do point to some broader enigmas worth puzzling over. For one, if the headshake is rooted in a “natural reaction”— to use their phrase—why does it emerge later than either pointing or waving, both of which are thought to be conventional? For another, if the headshake is rooted in rejection actions, why do infants not produce the signal until long after they produce the action itself?